The protective tissues cover the surface of the plant organs and are in contact with the environment. There are two main protection tissues: the epidermis in organs with primary growth and the periderm in organs with secondary growth.

1. Epidermis

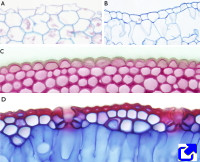

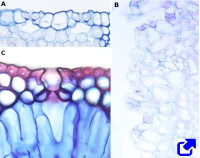

The epidermis is the outermost layer of plant organs showing primary growth, except for meristems. Although protection is a main function of the epidermis, it performs other functions, such as transpiration, gas exchange, storage, secretion, repelling herbivorous, attracting pollinators, and absorbing water in roots, among others. The epidermis is a tissue tipically made up of a one-cell-thick layer of cells. The most abundant cell type is the epidermal cell proper (or pavement cell), but other cell types are also present.

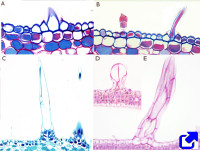

The epidermal cell proper is the more abundant and less specialized cell type of the epidermis. These cells are strongly attached to each other, with no intercellular spaces. Their shape and size are variable, having few or no chloroplasts, and they generally develop a primary cell wall. A protective layer called the cuticle typically develops on the surface of the free cell wall, which is the area facing the environment

Stomata are found in the epidermis. They consist of two guard cells that leave a pore, or ostiole, between them to allow gas exchange with the environment. Below the guard cells, there is an empty space referred to as the sub-stomatal chamber. Subsidiary cells surround the guard cells. All these components form the stomatal complex. Trichomes, or hairs, are specialized epidermal cells that extend as elongated projections from the epidermis. They may be for protection or for secretion (see the next page). In the root epidermis, some cells grow perpendicular to the surface and form root hairs for water and mineral absorption.

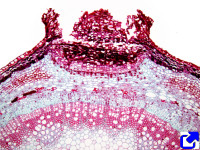

2. Periderm

The epidermis is replaced by the periderm in those organs with secondary growth. For instance, it becomes the bark of tree stems. The periderm is formed by the activity of the cork cambium meristem, or phellogen. It gives rise to cork outward and phelloderm (parenchyma) inward.

-

Bibliography ↷

-

Campilho A, Nieminen K, Ragni L. 2020. The development of the periderm: the final frontier between a plant and its environment. Current opinion in plant biology.53: 10-14. DOI:10.1016/j.pbi.2019.08.008.

Carpenter KJ. 2005. Stomatal architecture and evolution in basal angiosperms. American journal of botany 92: 1595-1615. DOI:10.3732/ajb.92.10.1595.

Javelle M, Vernoud V, Rogowsky PM, Ingram GC. 2010. Epidermis: the formation and functions of a fundamental plant tissue. New phytologist 189: 17-39. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03514.x.

Yeats TH, Rose JKC. 2013. The formation and function of plant cuticles. Plant physiology 163: 5-20. DOI: 10.1104/pp.113.222737.

Xue D, Zhang X, Lu X, Ghen G, Chen Z-H. 2017. Molecular evolutionary mechanisms of cuticular wax for plant drought tolerance. Frontiers in plant sciences 8: 261 DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00621.

-

Vascular

Vascular