Nowadays, we agree that organisms are made up of cells, but reaching this conclusion was a long way. The size of most cells is less than the resolving power of the human eye, which is approximately 200 micrometers (0,2 mm). The resolving power is the ability to distinguish two close points. For visualizing cells, it was therefore necessary the invention of devices that allowed higher resolving power than the human eye. This device was the light microscope. Light microscopes use visible light and glass lenses to increase the resolving power. The maximum resolving power of light microscopes is 0,2 micrometers, a thousand times higher than that of the human eye. But, even with the help of light microscopes, it took a long time to realize that cells were the units that make up all living organisms. This was due to the diversity of cell shapes and sizes, and also to the poor quality of the lenses that were part of the light microscopes crafted at that time.

1. Introduction

The history of the cell discovery started at the beginning of the 17th century, when the first lenses and the structures to use them for visualizing biological samples were crafted. That is, the light microscope was invented. The modern idea of the cell has been built over the years since, a process strongly connected to the crafting and refinement of light microscope, and therefore to the technology.

The following are some of the most outstanding advances and concepts in the history of the discovery of the cell:

2. XVII century

1590-1600. A. H. Lippershey, Z. Janssen and H. Janssen (father and son). They are credited with the invention of the first compound microscopes. Two magnifying lenses were placed at each end of a tube. The development of this device and the lens quality improvement would later allow the visualization of cells.

1610. Galileo Galilei described the insect cuticle. He transformed a telescope into a microscope by changing the positions of the lenses. So, he independently invented the compound microscope (he did not know about Janssen's work).

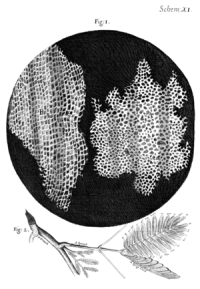

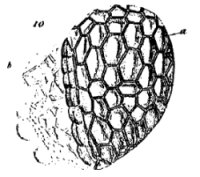

1664. R. Hooke (physicist, meteorologist, biologist, engineer, and architect) published a book entitled Micrographia, which describes the first evidence of cells. He studied the cork and observed an arrangement of plant tissue resembling a bee honeycomb (Figure 1). Each of those little compartments was named "cell" (from the Latin “cella”: small room), but he did not guess that these "cells" were the functional units of living beings. However, the word "cell" was used to name first the interior of those little chambers, and thereafter to name the units in animal tissues.

1670-1680. N. Grew and M. Malpighi studied many species of plants and described a similar microscopic organization for all of them. In the same way as R. Hooke, N. Grew described plant tissues, but the little chambers were regarded as fermentation bubbles (as in bread). He introduced the name parenchyma in plant and made many drawings about the organization of plant tissues. M. Malpighi gave names to many plant structures such as trachea (due to its similarity to the trachea of insects). These authors revealed the detailed microscopic organization of plants.

By that time, the lenses were of very poor quality, with large chromatic aberrations, and microscopists used to put a lot of imagination in their descriptions. In this way, G. d'Agoty saw a fully formed child in the head of a sperm cell, the homunculus.

1670. A. van Leeuwenhoek crafted simple microscopes, with a single lens, but with a perfection that allowed him to reach magnifications higher than 270 times, more than what compound microscopes could offer at that time. He can be regarded as the founder of microbiology because he was the first to report on descriptions of bacteria and unicellular eukaryotes. He observed drops of water, blood, semen, hairs, and many more. Moreover, he thought that all animals are made up of multiple units, but failed to associate these units with the cells of plants. Leeuwenhoek had named cells in liquid samples as "animalcules". Even after his detailed microscopic descriptions, many years passed before animal and plant cells were considered entities similar to the "animalcules".

3. XVIII century

Many improvements in the polishing of microscope lenses during the 18th century allowed much sharper images. The technology of better lens polishing begins in the 18th century and continued during the 19th century. C. M. Hall (1729) is credited with the discovery of a method to minimize the chromatic aberrations of lenses, that is, the dispersion of the light going through the lens. These improvements were first applied to telescopes. F. Beeldsnijder y H. Van Deyl (1791 to 1806) made the first microscope lenses without chromatic aberrations.

1759. The first attempt to put animals and plants at the same level was made by C. F. Wolf, who said that there is a fundamental unit with globular shape in all living organisms. In his book, Theoria generationis, he claimed that living organisms are formed as a result of progressive development and body structures appear by growth and differentiation of less developed structures. This theory was contrary to another very popular theory at that time: the preformationist theory, which suggested that a complete organism is already present inside each gamete, i.e. a fully developed tiny body that would get to the adult stage just by increasing the size of each part.

1792. L. Galvani discovered the electric nature of muscle contraction.

4. XIX century

In 1812, D. Brewester looks through immersion objectives for the first time. In 1820-1837, G. B. Amici further refined the lenses, removing more chromatic aberrations. He designed objectives with a resolving power and allowing a sharpness non seen before. His designs are currently used in the modern objectives.

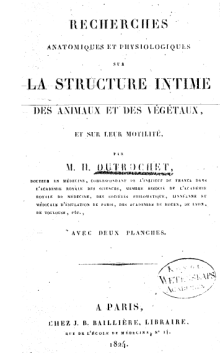

1820-1830. The development of the cell theory started in France with H. Milne-Edwards and F. V. Raspail. They observed a large variety of tissues from different animals and concluded that tissues were composed of globular and unevenly distributed units. Plants were also regarded as having these units. In addition, they claimed that these vesicles perform a physiological role. R. J. H. Dutrochet, French too, wrote if one compares the extreme simplicity of this striking structure, the cell, with the extreme diversity of its content, it is clear that it is the basic unit of an organized entity. Actually, everything is ultimately derived from the cell. He studied many animals and plants, and came to the conclusion that the plant cells and the globules of animals were the same thing, but with different morphology. He was the first to suggest some physiological functions for these units. F. V. Raspail, a chemist, proposed that each cell is like a laboratory that influences the organization of tissues and organisms. Finally, he said, previously to R. Virchow, "Omnis cellula e cellula", that is, every cell comes from another cell.

1831. R. Brown described the cell nucleus. This is rather controversial because in a letter reported by Leeuwenhoek in 1682, he described a rounded structure inside red blood cells of fish. This structure could not be anything else but the nucleus. However, he did not name it. Furthermore, in 1802, F. Bauer, from the Czech Republic, described a cell structure very similar to the cell nucleus.

1832. B. Dumortier described the binary division in plant cells. He reported the synthesis of new cell wall between the two new cells, and proposed that this mechanism was the way cells proliferate.

cell division

1835. R. Wagner described the nucleolus.

1837. J. Purkinje, from Czech Republic, one of the best histologist at that time, suggested the basic tenets of the cell biology theory, claimed that the animal tissues were made up of cells, and that animal tissues can be compared to plant tissues.

1838. M. J. Schleiden, a German botanist, wrote the first tenet of the cell theory for plants (he did not study animal tissues). That is, all plants are made up of units named cells. The German physiologist T. Schwann, in his book Mikroscopische Untersuchungen, extended this concept to animals, and later to all living organisms. He went beyond by saying that animals and plants follow the same basic principles.

Although the German school, T. Schwann and M.J. Schleiden, has been credited for the development of the cell theory tenets, there are at least four researchers who wrote similar statements years before: L. Oken (1805), Dutrochet (1824), Purkinje (1834) and G. G. Valentin (1834). R. J. H. Dutrochet stood out in the biology research field (see above).

1839-1843. F. J. F. Meyen, F. Dujardin and M. Barry connected and unified different fields of biology , and show that individual protozoa are nucleated cells, similar to those that make up animals and plants. In addition, they proposed that continuous cell lineages are the base of life.

1839-1846. 1839-1846. J. E. Purkinge and H. van Mohl independently proposed the name protoplasm for the content (excluding the nucleus and the cell wall) of plant cells. Plant cells showed a "cell membrane" (remember that this "membrane" was the cell wall plus cortical cytoplasm) that could not be observed in animal cells. Comparing plant and animals at the same level was not common in microscopy studies at that time. Then, when plant cells were observed in detail, it was proposed that the living part of the cell was the content of the tiny chambers, that is, the protoplasm. N. Pringsheim (1854) claimed that the protoplasm was the living matter of plant cells. Then, the living force was thought to be contained in the protoplasm in both plant and animal cells.

1856. R. Virchow wrote "The cell, as the simplest form of life-manifestation that nevertheless fully represents the idea of life, is the organic unity, the indivisible living one". By mid-nineteenth century, this theory was widely accepted.

The term "cell" and the idea of the "cell" as the living unit were not in good relationship during the 19th century. The protoplasm as living force was the "cell" content, what we know now as cytoplasm. During the 19th century, cell and protoplasm competed for the role of the anatomical and physiological unit of the living beings. Finally, the cell won the discussion. The word protoplasm has nearly disappeared from current biology textbooks. The discussion took place because researchers were looking for a place for the vital force (that is, where the life resides). Some favored the cell interior and others the whole cell.

1858. The use of dyes was a outstanding progress to discern and study the structures in biological samples, tissues and cells, at light microcopy. J. von Gerlach is credited with the first attempts by using carmin dye to study the nervous tissue.

1879. W. Flemming described the chromosome segregation and proposed the name mitosis.

1899. C. E. Overton suggested that the interface between the protoplasm and the extracellular space was lipidic. Based on osmosis and lipid diffusion experiments, he proposed the existence of a thin layer of lipids lining the protoplasm.

5. XX century

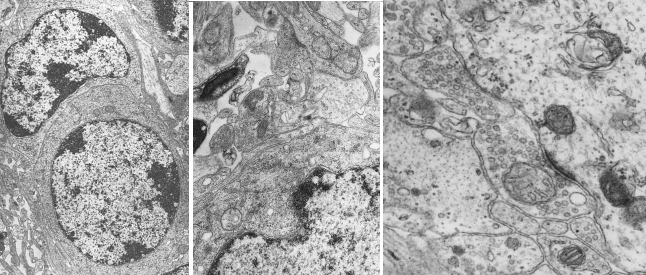

1932. The electron microscope was invented, and it was possible to study cell structures as small as several nanometers (10-3 micrometers) (Figure 5). The presence of the plasma membrane, and other membranes within the cell, was confirmed. It was the first time that cell membranes were observed. With the help of the electron microscope, it was shown that the eukaryotic cell were complex and rich in compartments. By 1960, the cell ultrastructure had already been studied and described.

-

Bibliografía ↷

-

Bibliografía

Cavalier-Smith, T. 2010. Deep phylogeny, ancestral groups and the four ages of life. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society B. 365: 111-132

Harris, H. 2000. The birth of the cell. Yale University Prerss. ISBN-10: 0300082959

Hook, R. 1664. Micrographia. US National Library of Medicine

Ling, G. 2007. History of the membrane (pump) theory of the living cell from its beginning in mid-19th century to its disproof 45 years ago - though still taught worldwide today as established truth. Physiological chemistry and physics and medical NMR 39: 1–67.

Liu, D. 2017. The cell and protoplasm as container, object, and substance, 1835–1861. Journal of the history of biology. ) 50:889–925.

http://micro.magnet.fsu.edu/index.html

-

Diversity

Diversity