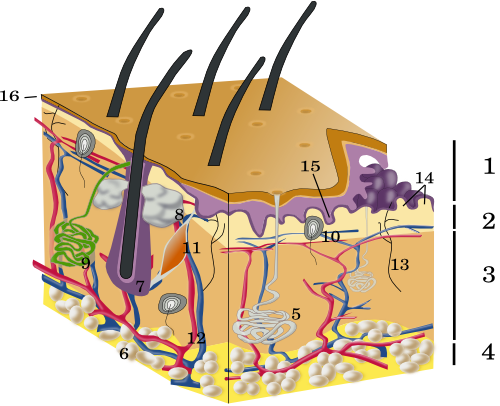

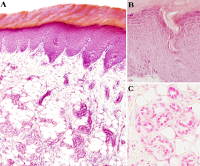

The integument covers the animal body. In vertebrates, it is made up of the skin and its derivatives and appendages. The skin has three components: the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis (Figure 1). Derivatives of the skin are hair, nails (scales and feathers in non-mammal vertebrates), and those glands that release their content on the outer body surface. When an area of the skin is under intense mechanical stress (pressure or friction), the epidermis and dermis increase in thickness. These areas are known as thick skin. On the other hand, those areas with thin skin show an epidermis with a few cell layers and a thin dermis. Thin skin is found in body surface areas under weak mechanical stress.

During embryonic development, the skin develops from the epidermal ectoderm, while the dermis and hypodermis differentiate from the mesoderm. In the fourth week of development, the embryo is covered by a cell layer and underlying messenchymal tissue. In the sixth week, these two tissues proliferate to form the skin. Hair follicles, nails, and glands appear in the third month of embryonic development.

1. Functions

The integument performs many functions. It is the main physical barrier of the body, protecting it from the external environment, and it is the largest sensory organ that gets information from the exterior. As a physical barrier, the integument protects against ultraviolet radiation, pathogens, and toxins, and it prevents water loss. As a sensory organ, the touch sense and the perception of external temperature are located in the integument. It is also a major regulator of the body temperature in many animals by allowing transpiration or protecting against cold by accumulating fat. The formation of vitamin D, which is important for the metabolism of bones, begins in the skin. Many substances, such as pheromones, are released onto the surface of the skin and allow chemical communication between individuals.

2. Epidermis

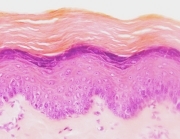

The epidermis is the outermost layer of the skin. It is a keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, mostly composed of keratinocytes. The epidermis prevents water loss, is a barrier against toxic substances, withstands mechanical stress, and is involved in immune responses. Keratinocytes form this barrier by making a cross-linked scaffold through cell-cell junctions. As a typical epithelium, the epidermis lacks blood vessels and rests on a specialized layer of extracellular matrix called the basal lamina. The basal lamina is produced by both keratinocytes and the underlying dermal fibroblasts, and it works as a barrier and as a adhesion element between the epidermis and the dermis.

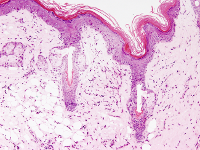

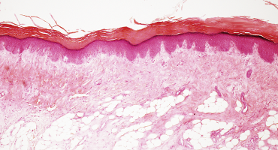

The epidermis may show different thicknesses depending on the mechanical forces it endures. For instance, it is thicker in palms and soles and also in other areas undergoing strong mechanical friction. Regardless of the thickness, the epidermis is divided into four layers, or strata. From the basal to the apical surfaces: stratum basale or germinative, stratum spinosum, stratum granulosum and stratum corneum. In the thick epidermis, an additional stratum, known as stratum lucidum, is observed between the stratum corneum and stratum spinosum. The stratum basale is where keratinocyte proliferation takes place. The new keratinocytes detach from the basal lamina and migrate upward while they differentiate to form the stratum spinosum. Finally, they die to become the keratinized dead cells of the stratum corneum. This is a rather complex process since there is a constant flux of cells from the basal to the superficial part of the epidermis for renewing and repairing the tissue, but at the same time there must be a tight cohesion between cells to make the epidermis a resistant barrier.

In the epidermis, other cell types are found intermingled with keratinocytes. Melanocytes synthesize melanin, which protects against ultraviolet radiation. In humans, there is a ratio of 1 melanocyte per 4 to 10 keratinocytes in the stratum basale. The higher rate is found in the genital skin. Langerhans cells, or dendritic cells, are derived from the bone marrow. They are up to 3–6 % of the epidermal cells in humans, largely found in the stratum spinosum. Langerhans cells are involved in the immune response as antigen-presenting cells. Merkel cells are found in the stratum basale and in the sheath that forms the hair follicles. They have a mechanical sensory function. These three cell types are more often found in the deeper epidermal layers. Keratinocytes develop from the epidermal ectoderm of the embryo. However, the other cell types are generated in other tissues of the embryo and migrate to the epidermis to later get infiltrated among keratinocytes. For instance, melanocytes are formed from the neural crest, an ectoderm-derived cell population.

3. Dermis

The dermis is a layer of connective tissue found under the basal lamina. The extracellular matrix of the dermis mainly consists of types I and III collagen fibers (more than 90 %). Reticular fibers are also present, and fibroblasts are the most abundant cell type. The dermis provides mechanical support and feeds the epidermis and skin appendages. There are protrusions of dermal tissue toward the epidermis known as dermal papillae, which are surrounded by downward epidermal expansions known as epidermal ridges. Both dermal papillae and epidermal ridges are easily observed in the thick skin. They increase the contact surface between the dermis and epidermis, reinforcing the adhesion strength. Two layers can be distinguished in the dermis. The papillary dermis, closer to the epidermis and in contact with the basal lamina, includes the dermal papillae, and it is connective tissue with abundant blood and lymphatic vessels for feeding the epidermis and to regulate the body temperature by vasodilation and vasoconstriction. In this layer, there are also many nerve sensory endings. Some of them cross the basal lamina and enter the epidermis. The deeper part of the dermis is known as the reticular dermis, which is dense, irregular connective tissue with fewer cells compared to the papillary dermis. However, it shows a well-developed extracellular matrix with more collagen fibers and thicker elastic fibers. The secretory components of the glands and most of the hair follicles are found in the reticular dermis.

There are two blood vessel plexuses in the dermis: one superficial in the papillary dermis and one subdermic under the reticular dermis. They communicate with each other through transversal blood vessels (perpendicular to the skin surface). The subdermal plexus is found between the dermis and the hypodermis and irrigates the hair follicles and sweat glands. The superficial plexus runs between the papillary and the reticular dermis and irrigates the dermal papillae. The lymphatic vessels begin in the dermis as blind ducts located in the dermal papillaries. The lymphatic vessels are formed of endothelium but lack basal lamina and pericytes. In the deeper lymphatic vessels, there are valves to prevent the reflux of the lymph gathered from the dermis. There is another lymphatic plexus between the papillary dermis and the hypodermis, known as the deeper plexus.

The Meisner corpuscles are mechanoreceptors found in the dermal papillae. The Vater-Pacini receptors are located at the dermis-hypodermis transition, and they detect pressure and vibration. The autonomous nervous system innervates the dermis with fibers coming from the sympathetic ganglia. These fibers activate the muscles of the blood vessels, hair follicles, and glomic bodies (involved in the blood pressure and temperature). Altogether, these nervous components regulate the vasomotor response, sweat production, and hair erection.

4. Hipodermis

The hypodermis is found below the dermis. It is also known as subcutaneous tissue or adipose panniculus. The hypodermis is mostly composed of adipocytes, surrounded by loose connective tissue. The thickness of this layer is variable depending on the body region and age, and it is also different between men and women. The head lacks hypodermis, so the dermis is in contact with the cranial bones. The arrector muscle (smooth muscle cells) of hair can sometimes be found in the hypodermis, and a few striated muscle cells are present in the hypodermis of the neck and face.

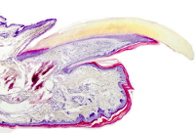

5. Derivatives

In mammals, the epidermis derivatives are nails, hair, and glands. All of them are formed by induction signals coming from the underlying dermis. Hair grows in epidermal invaginations, known as hair follicles, which are irregularly distributed through the skin of the body. Sebaceous glands, which are part of the hair follicles, and apocrine sweat glands release their content into the lumen of the hair follicle. Eccrine sweat glands, however, release their content directly on the surface of the skin. These glands are distributed all over the body surface. Nails are hard and compact layers of keratin located in the dorsal part of the fingertips. In other species, other epidermal derivatives can be found, such as horns, scales, feathers, and hoofs.

-

Bibliography ↷

-

Khavkin J,Ellis ADF. (2011). Agin skin: histology, physiology, and pathology. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 19: 229-234.

-

Senses

Senses